Political Frenemy

Rami Karim

We leave the grocery store with four beers as an alternative to paying three times as much for just one at the bar. I ask Amal if we should prep Maya for her arrival and she says it’s unnecessary since we’re beyond that elementary flavor of identitarianism, implying that Maya would not be fazed by the racism she may encounter here because she’s smart and cultured enough to know Beirut is not like New York, that there are different rules and it might even be imperialist for her to take offense. Moments earlier we’d discussed how racism happens differently in Beirut. The liberal American kind we’re used to functions in disguise but here it’s often unabashed. Passive aggression becomes plain aggression. I wonder which is worse as we take our seats.

At the airport I worry when Maya hasn’t shown despite the monitor noting that later flights have landed. Amal’s at work so I’m here alone. Maya exits just after sunset in a slow fluorescent trance. I call her name but she doesn’t hear. I whistle, it’s ineffective. I yell Maya! in an obtuse manner and she turns in my direction. Her eyes are sunken but she manages a smile.

Maya grew up in Oakland and prodigiously began covering national politics for the San Francisco Chronicle at 14. She received a full ride at Columbia to study politics and now produces a nationally acclaimed column and advice podcast while heading a media consultancy. On the ride home she explains that the border guard questioned her for what seemed like hours, he wouldn’t believe she was visiting friends. She tried to text but couldn’t roam and had run through the airport’s free wifi. I grow anxious as she gets into specifics. It sounds like she’s trying to psych herself out of something. She says that when she showed the guard my address he remained finicky and said it was technically the address of a bakery across the street from my apartment, knowing full well that formal addresses are rare in Beirut. Eventually Maya asked why this was taking so long and where her passport was. The guard told her to stay calm: You want to go through, yes? as if to say it would just be a matter of time if she’d only shut up and let him finish the nonsense he was performing behind the counter. So she waited, and after an hour he returned her passport, which she accepted with a smile and thank you.

We finally reach Amal’s apartment and look for empty patches of floor in her room to lay out a mattress. Maya appears drained and her mood is on the brink of melancholy but our not having seen each other since August allows us both to hold things together. A friend of Amal’s boyfriend named Christine enters with a Hey that interrupts the silence. Christine is visiting from London where she’s finishing a cultural studies master’s. Maya and Christine engage in smalltalk that feels laced with a tension I can’t articulate. After pleasantries Christine becomes aloof, checking her phone constantly and looking out the window when she isn’t.

Upon arriving, Amal and Maya talk emphatically about how long it’s been before asking about each other’s days. I briefly wonder if my difficulty sustaining visible affection for friends means something’s wrong with me before concluding that I’m being neurotic; if a friendship needs coddling it’s probably not a worthy one. Maya pulls out a suitcase she says contains the things we ordered and lays it open on the floor. She says she didn’t pack much of her own stuff so she could fit ours. I become guilty despite knowing it brings her joy to help. I take my Levi’s and bottle of rosehip oil to my room and return to Amal trying on a pair of Reeboks she’d ordered. I can tell they don’t fit by the look on her face. She pouts and says they’re too big, pressing on her big toe to demonstrate. She tells Maya she’ll have to take them back to New York for a refund. Maya says she threw the box away and Amal replies that any box will do, they just have to go somewhere.

Being in public has been different with Maya here. After breakfast in Mar Elias we walk down the main road and a group of teens playing alleyway soccer stop to stare. They ask out loud who Maya is, what she’s doing here and who I am to be with her. I translate and Maya replies that this is manageable, like that time she was in Mexico with her ex-boyfriend. She says harmless curiosity isn’t worth being offended by. This is a working class neighborhood right? I answer yes and she says yeah.

The next morning we are scheduled to visit Hezbollah’s Tourist Landmark of the Resistance in Malita after meeting Amal’s boyfriend Yousef in Ain El Mraiseh. He’s applying to philosophy programs in Europe and shares an apartment with four other 20-something philosophy bros. Amal’s been talking him up since they met in August. He and I met last week and argued about where the line between analytic and continental philosophy is drawn until I snapped out of humoring care and passively agreed that it was Heidegger, bearing in mind his culture bracket’s autopiloted infatuation with problematic idealists and knowing full well it was in fact Hegel, though as my friend Elena says, only retrospectively. Yousef greets us by pecking Amal’s cheek and saying this is Maya? to which Maya awws and goes in for a hug before he grunts, points at his throat and looks at Amal who says oh I totally forgot, he’s sick. In the living room Maya and I giggle about the attention she’s been receiving in public. Christine chuckles and says yeah, people of your color are treated like this here. We say they’re not intrigued because she’s black but because she’s stunning. Christine says only domestic workers share her skin tone, that these men were probably wondering who she was to dress that way, where she could possibly be going and so on. Amal says nothing. Maya looks at me with rolled eyes and interrupts by asking for the wifi password.

At the Malita exhibition we watch a short propaganda film showing unedited footage from the 2006 war with Israel. Maya exits after five minutes and I follow. She says it’s become nearly impossible to watch violence while remaining unfazed. Amal and Christine exit half an hour later and say they teared up out of reverence. From the way they talk about Hezbollah I conclude they think it’s good to love them for their anti-colonial politics and hate them for aiding Assad in Syria. It was just so emotional, Christine says, I lived through 2006. Suddenly the words as someone who become frontal in my mind and I consider how anything can be made into an identity, especially trauma.

We’re at dinner with Amal’s artist friend Jad who tells us about his new virtual reality project about utopic queer spaces in Beirut, void of straight and white people. Maya asks if there are that many white people in Beirut. It seems like I rarely see them? I say it’s mostly tourists and nonprofit workers though even then, the numbers are miniscule. I find it strange that Jad and Amal are friends because they appear on opposite ends of a (very niche) political spectrum. Jad is deeply invested in identity politics and Amal claims to detest them despite leaning way into her Syrianness whenever the conflict is even peripherally mentioned.

Maya and I spend the week passively sightseeing and talking about the men we’ve seen since summer, our work, our spirals. We find out we’re both searching for structured spiritual grounding to curb our nihilism. We rent a car and drive to Tyre. We have lunch on the Corniche with my mom. On her last morning Maya points out that it’s just been the two of us since Malita. Amal has mostly been at her boyfriend’s. Maya asks what’s going on with her? To my own surprise I start by defending Amal. I say she’s in love and attached to her boyfriend in an understandably juvenile way before realizing I’m just as bothered. I’ve been keeping my critiques to myself and decide it’s now appropriate to gossip.

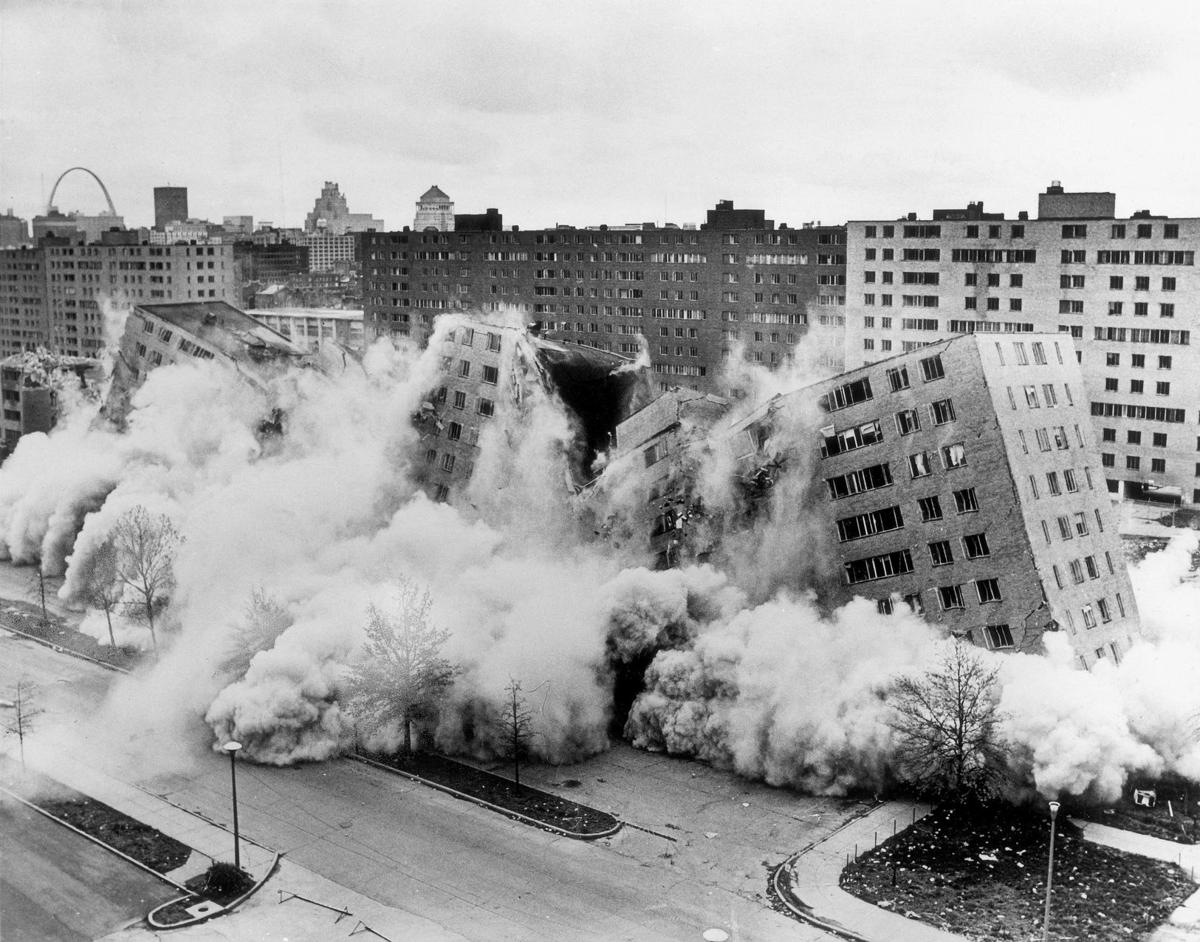

I start by saying Lebanon is majority-brown and stratified along sectarian and economic lines. Whiteness doesn’t correlate to phenotype because there aren’t enough white people to make up a dominant bloc. Structural difference instead looks like religious and class hierarchy. We circle back to Amal. Maya says her friend Jad is a secretly rich Instagram artist who uses identitarianism to evade implication in the systems he attempts to critique. She says this is the same shit as Fanon’s assimilation theory except with rich brown people self-fetishizing their identities to maintain an amnesiac bubble against class violence, which then extends into cultural production. She says Fanon diagnosed a feeling of inferiority among colonized people that they sought to overcome by wearing European clothes and integrating western vernacular—material adjustments toward psychological alignment with whiteness. I say this reaction to hegemony still occurs in Beirut, though often dressed in signifiers from liberationist struggles that make it ostensibly allergic to criticism. We conclude that Amal is different from Jad, though they both use supremacist evasion tactics. Amal was raised upper class in San Diego. A daughter of two doctors, she drove a Mercedes, went to private schools and only wore designer. The catch is that she was also raised doctrinally Sunni and only stopped wearing hijab a year ago, which coincided with self-identifying as atheist. Now she and her aesthetically poor but actually rich boyfriend-adjacent crew front Trotsky in a way that overlooks actual racism, so hot that it’s cold. Meanwhile Jad builds an art career by importing American race theory into Beirut when he should instead consider class, which even Amal, a self-proclaimed communist, ignores.

We sit with the gossip until it stops being useful, let alone fun. Maya defeatedly calls it water under the bridge as she folds her clothes that evening. On our way to the airport she adds that Amal uses being technically Arab to hide being culturally white. I don’t know when we came to understand cutting personal ties as activism. Maybe it’s in response to our failed efforts at actual organizing. Maybe failing yielded a depression or laziness that made cutting ties feel worth patting our backs for. I assure Maya that her trip wasn’t totally useless, at least we had a week of quality time. I say there is no love where there is transaction, that you can feel love like you feel heat or that thing we call good politics. Maya leans against the window in silence. As the car pulls up she asks when I’m coming back and I reply not before I finish the book. She sighs and grabs her suitcase from the trunk. Let me know when to pick you up.