Architecturing Borders

Fernanda Carlovich

Embedded in the Luz neighborhood, in the middle of what is often referred to as São Paulo’s cracolândia (crack-land), is the Container Theater, an independent performance space conceived and built by the Mungunzá Performing Arts Collective. The collective is comprised by actors that have been producing plays about social and political issues over the past 10 years. This is a case study of how the architectonic decisions of the Container Theater, from its location to its use of openings and enclosures, complicate the relations between the theater, the Luz neighborhood, and its population.

CONTAINERS

Containers have taken up different spaces in cities, evolving far beyond their original shipping function. The ease with which they are transported and assembled, combined with the infinite possibilities of their modularity, turned this transportation item into a construction system. From container cafes and pop-up stores, to container emergency houses and jails, “cargotecture” has become an important architecture niche over the last decade. In the essay Container Aesthetics, Michael Shane Boyle highlights the social adaptability of containers and observes that “they are as fit to be playgrounds for the rich as they are prisons for the poor.”1 In the essay, Boyle also questions their ubiquity as a fast answer to construction. Further, it is clear that the use of containers, depending on the purpose and context, can be related to a certain aesthetic, one that may have begun with improvised urban leisure areas and evolved into a “hype.”

On October 30, 2016, 11 containers landed in a public space in downtown São Paulo. Out of a giant stacked puzzle, and with the help of a crane, emerged the Container Theater. Responsible for its ideation was the Mungunzá Performing Arts Collective, which began as a traveling group of actors who eventually pursued a fixed location to constitute their theater and rehearsing space. For this, the collective obtained permission from the city hall to use what was at the time an officer parking lot in front of a police station. They began this project as part of a three-month festival called Architecturing the City;2 by the end of the festival, the group had completed the Container Theater and started occupying the space illegally.3

The theater is an architectural project that emerged purely from the empirical knowledge of the actors and their experiences in other performance spaces. The resulting space expresses a lot more than just its function. With capacity for 100 sitting and 300 standing people, the main structure surrounds the high-ceiling stage and counts with a small cafe on the ground floor and a dressing-room above. All the furniture inside seems temporary, made with metal scaffolding structures and unfinished wood. The temporary and makeshift aspect can also be seen beyond the main structure—between the limits of the fenced terrain and the piled containers, an interstitial space holds benches made out of trash cans, pallet tables, and small recreational equipment.

The most intriguing aspect of the Container Theater’s architecture is the stage, which is surrounded by glass façades that incorporate the movement on the street as a part of every show performed. The Container Theater’s appropriation of a particularly vulnerable area of the city as its scenery, illustrates how the use of cargotecture aesthetics—under the guise of Mungunzá’s premise of generating socio-political discourse—enacts a violence towards the community that dwells near the theater.

So-called cracolândia combines bodies and activities associated with the consumption and sale of crack cocaine in São Paulo; it is a chaotic territory occupied by one of the city’s most vulnerable populations. The appearance of a theater in this context raises a series of complex issues: the privileged notion that the theater is somehow bringing “culture” to a degraded area of the city, the increase in circulation of middle-class people and what it entails for this area, and the ensuing “demystification” of the dangerous character of Luz. The glass façades of the theater attempt to enable an experience that is parallel and literally transparent to its context from within a protected space that is socially in contrast with the surroundings. The interstitial space between the fences and the theater is occupied by middle-class youth who hang out in groups, drinking beer and listening to music while waiting for the play. They are occupying this territory, but separated from it. When the show begins, the audience, protected by glass, sees the figures of those who are a part of this region, perhaps unaware of their role in the spectacle’s aesthetics.

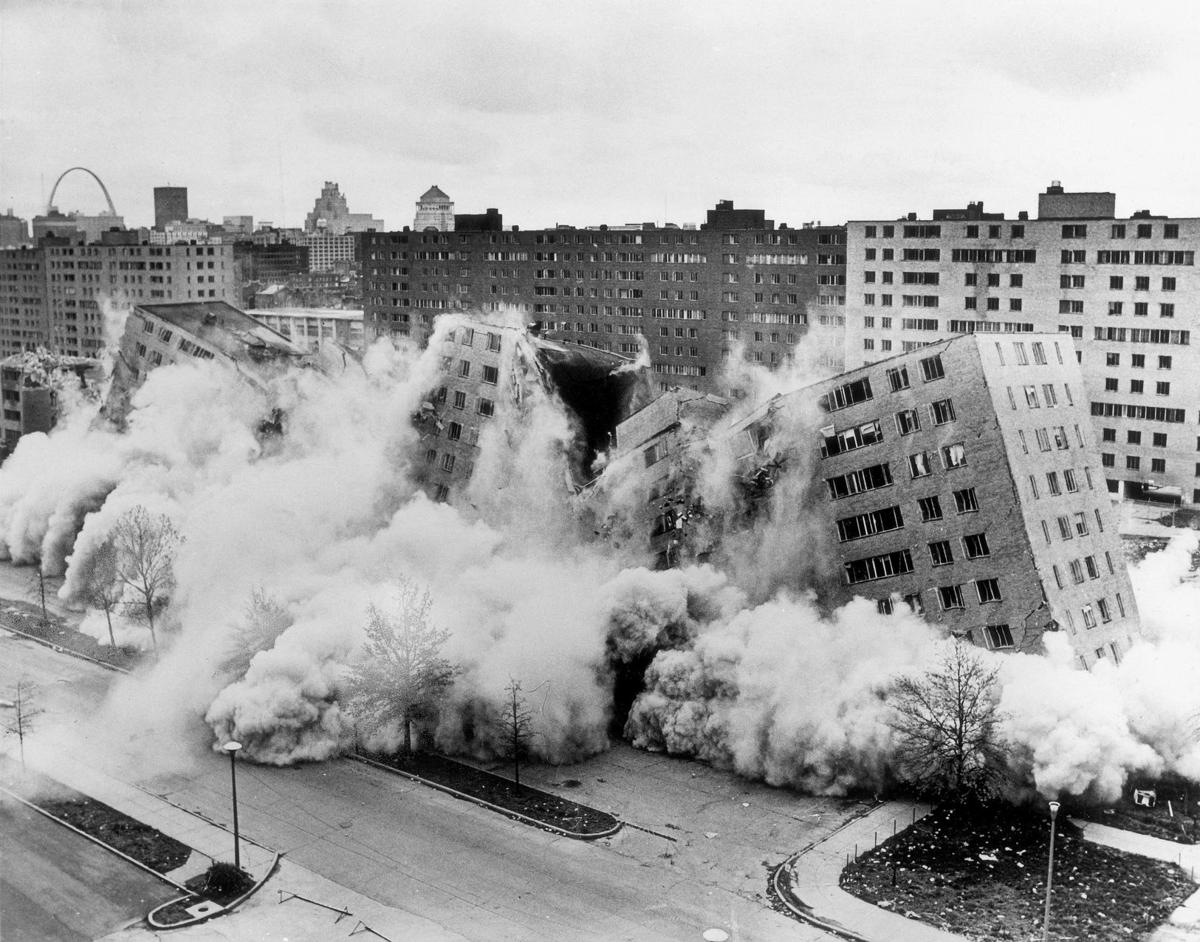

It is possible to argue that the run-down character of the area—with irregular constructions, abandoned buildings, and pixos4 all over the walls—creates the perfect backdrop for the aesthetics that the group seeks to achieve through their theater made of colored containers and trash cans. It is important to distinguish that the character of the neighborhood is the outcome of a self-constructed community, whereas the cargotecture aesthetic that Mungunzá engages is a conscious quest for an “improvised” aesthetic—one that is essential in attracting the target audience to their events: middle- class youth in search for a cool “underground” venue in which to party. This hipster character communicated through industrial aesthetics correlates the Container Theater with other places in the city that share not only the same appearance but also the same gentrifying stigma: Bars, restaurants, galleries, and stores change the character of a neighborhood, stimulating real estate interest, inflating the cost of living, and driving out the neediest dwellers. While this phenomenon is harmful anywhere in the city, when viewed within such a precarious community like the drug-affected district in Luz, it is even more jarring.

FLOWS

Movement has marked the Luz neighborhood since its establishment in the second half of the 19th century, when the area housed the first railway station of São Paulo. The station was a focal point for the city, and the neighborhood benefitted from the development of urban squares, tree-lined streets, and cultural facilities such as the Pinacoteca do Estado (one of the most important art museums in Brazil). With time, the noise of the trains and the high flow of goods drove wealthy residents to other districts, and the region started to become occupied by low-income workers and small family businesses. This was followed by the emergence of tenements, the establishment of a prison, real-estate speculation, and a segregating highway project—factors that ultimately contributed to the neighborhood’s degradation over the 20th century.5

It is against this backdrop that, in the beginning of the 1990s, the consumption and sale of crack cocaine arrived to the neighborhood. Exchange, circulation, and rapid dispersion characterized the neighborhood long before the flow of crack cocaine arrived. Nowadays, the Luz region combines a variety of different flows: the flow of goods; an immense flow of people from the subway station, train station, and bus terminals; and the flow of the crack cocaine market. It is a highly complex urban territory where scenes of political disputes and an overlap of different interests take place.

Although it is common to confuse the limits of the Luz neighborhood with the so- called cracolândia, the latter is an even more complex territory to define. While Luz is a neighborhood with physical boundaries and a precise location, the commerce of crack cocaine exists as a field of relationships that accompanies the movement of people involved in all the activities associated with this market: the commerce of drugs and related products, the trade of stolen items, the renting of beds in tenements, and prostitution.6 It is the association of bodies and their practices that defines the vulnerable condition of the place, a simulacrum of social behavior into territory.

The Luz neighborhood hosts a great number of cultural institutions founded during the region’s wealthy period and followed by state investment during the 1980s. The latter includes the renovation of Pinacoteca do Estado, the refurbishment of an old train station into the São Paulo Symphony Orchestra Hall, the Museu da Resistência (a memorial to the resistance of Brazil’s military dictatorship), and the Portuguese Language Museum, among others. Thus, Luz can be understood as a double-character region: it attracts both an influx of middle- and upper-class people for cultural consumption and, at the same time, hosts the stigma of degradation and crime.

WINDOWS

In 2015, Lebanese artist Mona Hatoum did her first solo exhibition in São Paulo at Estação Pinacoteca, a few blocks apart from the site that would host the Container Theater. Inspired by the complex scenario of the Luz neighborhood, the artist created a work called Janela (“window,” in Portuguese), where she positioned a camera outside the museum and reproduced the footage in real time inside the exhibition space. She intended to create a virtual window between the different worlds that interweave in the region, and in doing so expose and question the apparent blindness of the middle class toward the community that lives in the area. Generally, the population that frequents these cultural activities arrives and leaves by car and does not circulate on foot through the neighborhood due to the stigma of violence and fear, combined with a heavily policed system that prevents these two communities—users of crack and visitors— from crossing. Hatoum’s installation and the Container Theater’s glass stage are both attempts to construct forced contact between those groups, a window between spectacle and reality.

This duo of projects—Hatoum’s Janela and the Container Theater—exemplify two extremes of “socially engaged” art. In the case of Hatoum, her work is not intended to connect these two worlds beyond a reflexive field; her windows are metaphorical ones and open up discussions only for those who visit the exhibition. In the case of the Mungunzá collective, the boundaries between their performances, the subjects of study, and their realities are entirely merged. For example, one of their plays in 2018, titled Silver Epidemic, explores the lives of drug users from the Luz neighborhood. They are being represented by the actors on the stage, while the users themselves are moving around the theater, often stopping to watch the show from the outside. The proximity between acting and reality in this case exemplifies the extent to which artistic expression can ruthlessly take advantage of an already vulnerable context to support its purpose. In this case, the lack of limits between the represented subject and the representative subject overpass whatever may have been the intentions for social critique of the actors to become instead an expression of invasiveness toward those who are being depicted on the stage and used as props on the streets.

More than visual connections, windows can represent the way we look at the world: they can cover or showcase information. This is apparent in the apathetic manner in which the police officers reacted to the illegality of the construction that was taking place right in front of their station. In a community marked by extreme police violence, this immunity relates to the intrinsic privileges of the group: primarily young, white, middle-class men. Would the police have reacted with the same blindness if members of the local community were holding the construction? Most certainly not. What are the windows that frame the police’s vision in this context? This “civil disobedience” performance—as the Mungunzá group described the illegal occupation of the police parking lot—was only possible because the group was aware of their privilege and was not afraid of punitive consequences. Perhaps this is the most significant difference between the theater group and the local community: the windows through which they are perceived.

The glass is an emblem of the social impermeability that divides the two communities occupying this area of Luz, and the forced visual contact that occurs between them: it is a physical barrier and a visual opening. The way in which the different elements that constitute the theater were chosen and combined, especially with the full-length windows, exacerbates the contrasts between the experiences that occur inside and outside that space; a gesture that at first may seem of openness ends up revealing the oppressiveness of its act.

FENCES

The Luz neighborhood has a double character that generates two flows of people: those that enter and leave cultural spaces by car and those who live there. For this reason, all the museums of the region are surrounded by chain-link fences in an attempt to create a sense of safety. A fence of this sort, unlike a wall, does not absolutely divide a space—it allows for a visual and, for the athletic or willful, a physical permeability. More than an element that effectively guarantees security, the fence is a marker of who can and cannot exceed its limits. It is symbolic protection invested with segregation.

During the Architecturing the City festival, the city requested that the Mungunzá group keep the fence that already surrounded the lot and the group obliged. In the morning, before the theater opens, children from the neighborhood jump the fence to use the outdoor space as a playground. As they lack other quality public spaces in the area, this has become an essential one for them. However, that they have to jump the fence to access this theoretically public space is further evidence of the exclusionary characteristic of the theater. Giving the community control over the gate could be one attempt in resolving the issues of access and belonging.

The strange relationship between the metal fence that surrounds the theater and the glass chosen to encompass its stage transmits a message: the outer fence safeguards the theater from the drug users while the internal glass allows those users to be viewed as if the existence of these people was intriguing only from a safe point of view. It is an architectural act of both segregation increased proximity between those different members of São Paulo’s society; the arrangement of bodies and their privileges, or lack of, translated into space.

The ambiguities between openings and enclosures, public and private access, visual permeability and physical barriers all indicate that the theater’s spatial conformation ultimately does not successfully achieve the theater group’s expressed intention to engage with the community. The members of the group are aware of the several vulnerabilities of their surroundings, and in an attempt to ameliorate this, they have developed a series of activities involving the population of the region: they host lectures, discussions, and neighbors’ meetings. Still, these actions should not give the group carte blanche to insert themselves into this complex urban dynamic—these activities are a self-serving measure following the violent conquering and aesthetic appropriation of the neighborhood. Architecture carries political positions, prejudices, and ideologies that are sensitive to its surroundings, funds employed, and the interests behind its realization. Ultimately, it can blur or reinforce boundaries, and the difference between these actions is not as simple as creating a window to connect or a fence to divide. If the architecture of the Container Theater is to be a reflection of its agents and their socio-political intentions, then it must be retooled within a new social configuration. The future of the Container Theater should not be its demolition, for it could function as a rare cultural space that connects with the true residents of the neighborhood it exists within. What needs to change is the bodies that occupy this space and the stories they have to tell.

-

Michael Shane Boyle, “Container Aesthetics: The Infrastructural Politics of Shunt’s the Boy Who Climbed Out of His Face,” Theatre Journal 68 (2016): 58. ↩

-

Despite being advertised as a theater festival, the “festival” was the realization of the building’s construction, interpreted by the group as a major guerrilla performance. ↩

-

After one year of existing in the space, the group got the municipal permit to occupy the grounds for three more years. ↩

-

“Pixo” exists in a hostile relationship with the environment it occupies, and unlike graffiti, is more related to a form of protest than a search for an aesthetic expression. It consists basically of signatures (of people and groups) that compete for space and visibility in Brazilian cities. Pixo is an explicit critique of urban inequity and, because of that, its existence is mainly seen as an “invasion” that signals an unsafe environment. ↩

-

Eudes Campos, “Nos Caminhos da Luz, Antigos Palacetes da Elite Paulistana,” Anais do Museu Paulista: História E Cultura Material 13, no. 1 (2005): 14. ↩

-

Heitor Frúgoli Jr. and Enrico Spaggiari, “Networks and Territorialities: An Ethnographic Approach to the So-Called Cracolândia [crackland] in São Paulo,” Vibrant 8, no. 2 (2011): 554. ↩