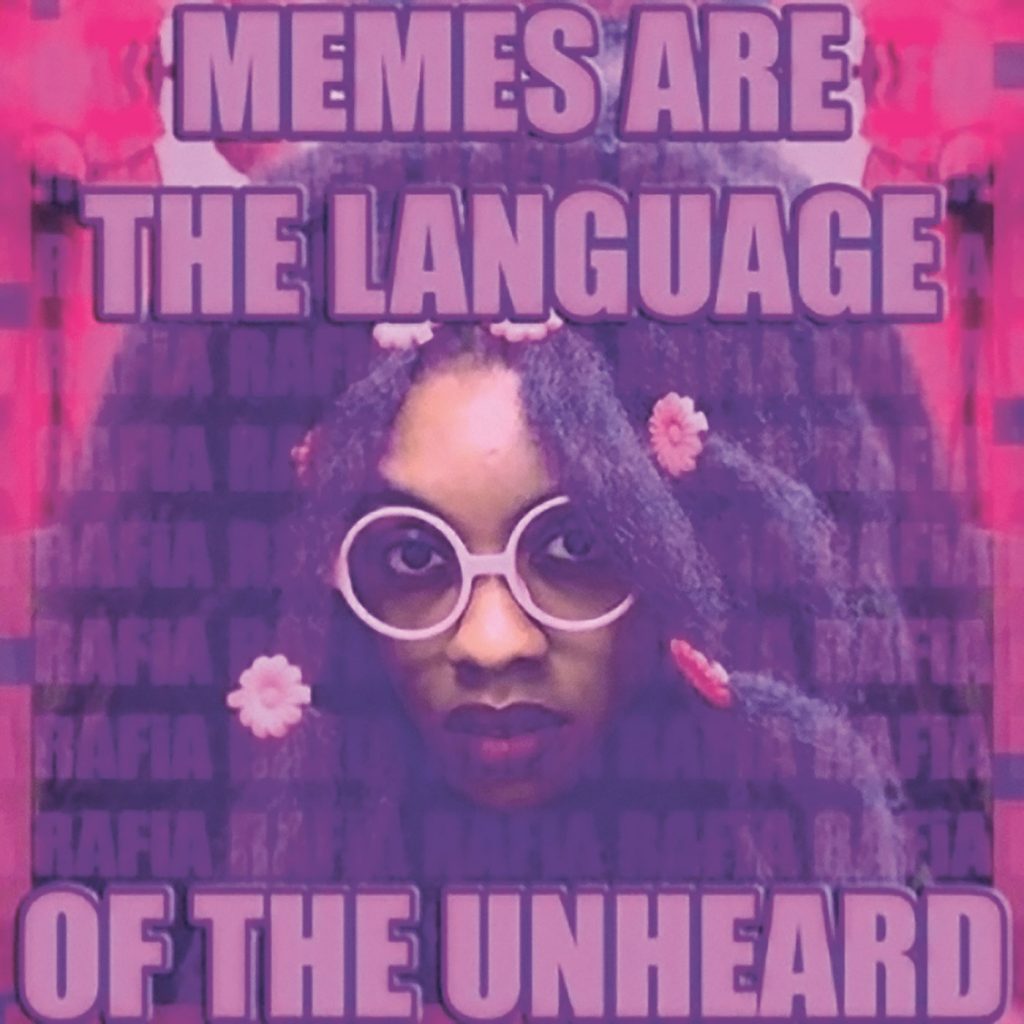

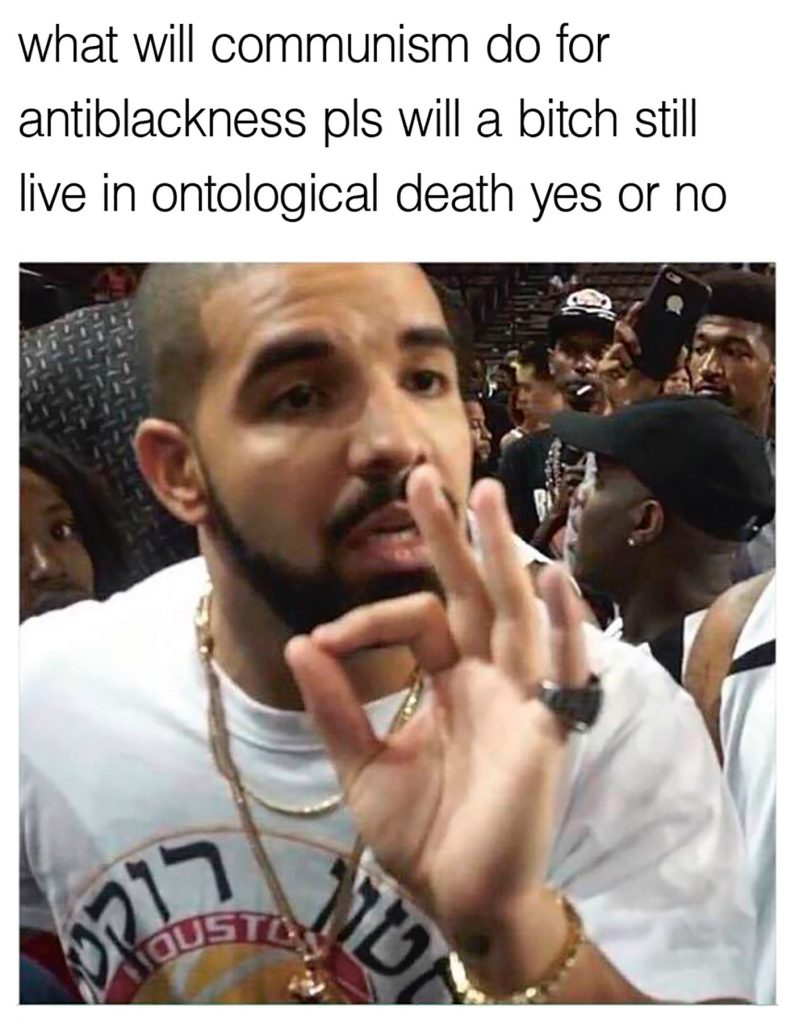

Do you remember when people misheard the words “fuck that” on the chorus of Kendrick Lamar’s “A.D.H.D.” as “fuck thought?” Well, fuck thought. Kind of. Let’s talk about it.

1. Reanalyzing the Thought Fetish

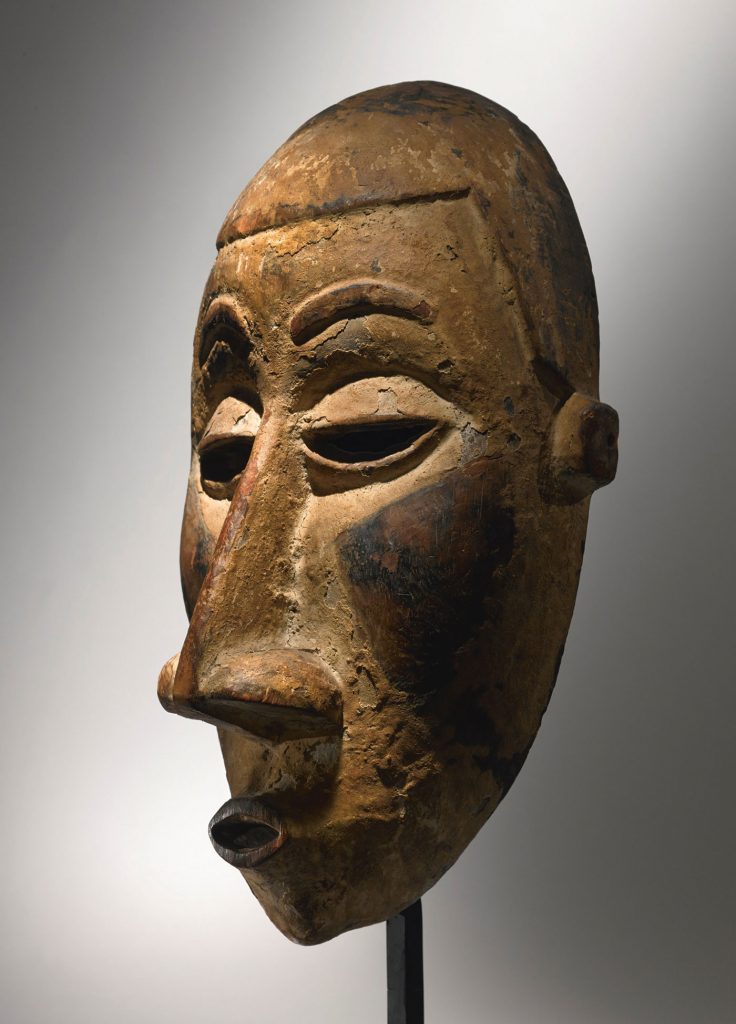

By means of ‘lack of reason’—with religion, language, appearance, and other aspects serving as a litmus—the animalization of Black and brown people has been a critical tool of domination, invented to justify the white conquest, genocide, slavery, and other violence that engendered the contemporary.

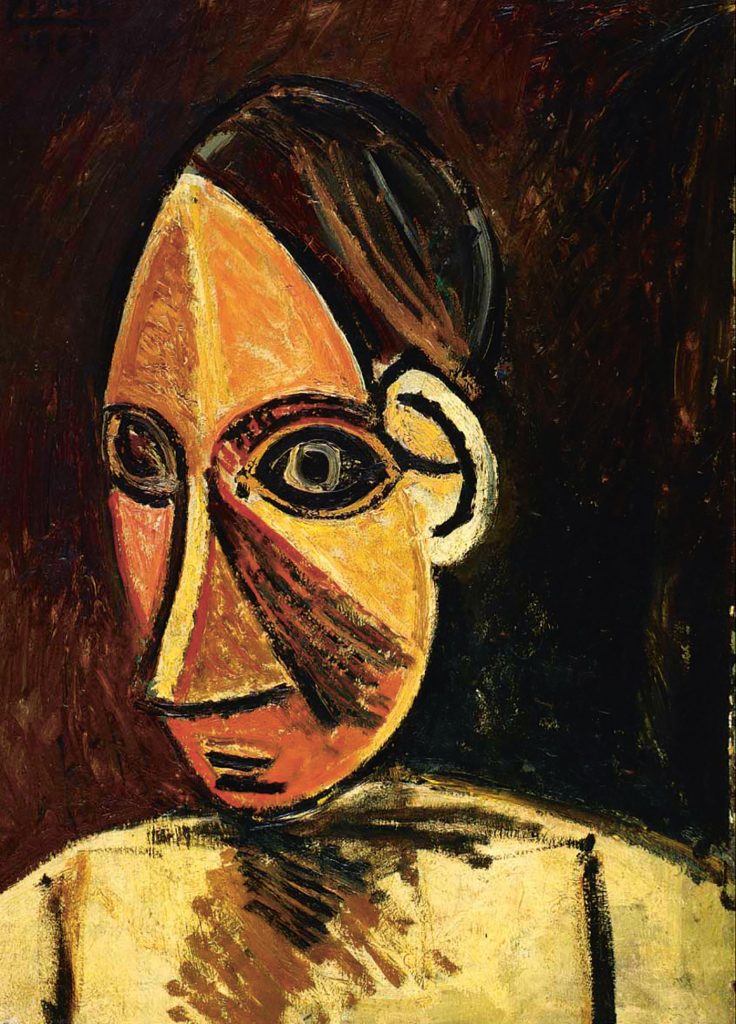

What does it mean, then, that art today prizes thinking and the aesthetics of thought such as criticality, divestment from the sensory, and a demeanor of philosophical objectivity? The white West used these very criteria to dehumanize the global south and facilitate Euro expansion; in a specifically aesthetic context, modernism itself was premised on the spoils of imperial conquest.

Despite clarion calls of posthumanism, it is possible to excavate an exclusionary humanism in the fetishism for ‘objective philosophical thought’ in contemporary art which preserves the modernist dynamic of treating Black and brown people and aesthetics as raw material. We can recalibrate our definitions of art from the contemplation and production of the beautifully useless and self-referential. A continued utilitarian project of the violent subsumption of non-white aesthetics is possible through reading Allan Kaprow’s concept of post-art in the context of the Middle Passage and its afterlife.

2. The Contemporary

David Joselit defines the contemporary as a mode of aesthetic governance relegating marginal practitioners into a position of debt to modernism. For Joselit, this imposition of debt mirrors governance by debt in neocolonialism, rendering what he calls heritage or local context merely a dividend of debt, serving to diversify the art market and globalize its structural tropes (such as painterly abstraction, the white cube, the biennial, etc).1 Joselit, “Heritage and Debt” (lecture, Mack Lecture Series, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, December 3, 2014), February 12, 2015

Joselit’s analytic is useful for unearthing not only the originary violence of modernism with respect to Black and brown aesthetics, but also the ways the contemporary continues this project of subsumption.2As part of Home School—a free pop-up art school I co-facilitate in Portland—I taught a class called Contemporaneity: building a better white supremacy, which further explores these ideas. Aesthetic governance by debt allows the increasingly marketized art world to commoditize difference and deploy it for its own ends, whether financial, nationalist, or otherwise.

Yoked under modernism, marginal artists must assimilate to standard aesthetics3“I call ‘standard’ those aesthetics whose principles (1) are recognized and accepted, across a number of variations, by institutional and academic communities and which thus constitute the object of confirmed knowledges; (2) whose principles define either a foundation for art or a philosophical description of art or, more generally, a normality and a normativity; which is to say (3) a determinism of the reciprocal causality of art and of philosophy. It poses well known questions of the type ‘What is art?,’ ‘What is the essence of art?,’ ‘What can art do?,’ and it believes it can answer these questions with certainty. In accordance with these questions, standard aesthetics describes the styles, forms and historical epochs of art in a broadly realist manner, for it believes it is possible to define both art and philosophy.” Laruelle 2012 and allow themselves to be deployed in service of institutionality. At a deeper level, aesthetic governance by debt allows art to deny modernism’s own constitutive debt to Black and brown aesthetics, which it used as raw material to shirk the constraints of earlier white art such as three-point perspective and objecthood.

The contemporary is an echo of modernism, it continues the edict of modernism while developing new forms of governance over marginalized artists.

3. The End of Art

In the afterlife of conceptualism, thinking overcame and reframed making, and embodied a Hegelian assumption of teleological human evolution, such that Western society has outgrown the stage at which art is the supreme mode of our knowledge of the Absolute. Hegel says “We have got beyond venerating works of art as divine and worshipping them… Thought and reflection have spread their wings above fine art.”4Hegel, Hegel’s Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Arts, Vol. 1, 10. With respect to art, Hegel focuses on the contemplation of beauty, but for our purposes a tautological definition of art as whatever is called art works fine.

During Western industrialization, art’s dependence on the sensory caused it to fall behind thought as the highest vocation and prime engine of knowledge, whose “very essence… is to go from the observable to the non-observable, from the immediate to the mediate.”5Kaminsky, Hegel on Art: An Interpretation of Hegel’s Aesthetics, 8. For Hegel, human cultural developments like art and religion are vestigial forms, reflecting an older dependence on the sensory before the modern mastery of nature represented by industry.

For Hegel’s teleology, art is over, but it remains a necessary step in human development: aesthetic contemplation and production indicate the gradient between human and non-human, setting the stage for reason to flourish. It is precisely the intimate revelry of the sensory which, when refined, allows for the philosophical flight into the immaterial, the theoretical, and the nonsensory. Without art, philosophy could not have risen.6Kaminsky, Hegel on Art: An Interpretation of Hegel’s Aesthetics, 27.

4. The Conceptualist Gambit

By dint of art’s putative necessity to human development, conceptualism attempted to salvage the patrimony of Western art by ushering thought itself into the set of available artistic mediums.

From this lowered position, modernist aesthetics worked to expand the boundaries of what could be institutionalized as art. Conceptualism went further, and deployed the autonomous inutility of the art object inherited from modernism to show how, as Allan Kaprow states, “art has served as an instructional transition to its own elimination by life.”7Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, 102.

While this may have partly emerged from idealistic notions of thought as medium precluding subsumption into the commodity form, the result was that the subject and role of art—which for Kaprow was “the ritual escape of Culture”—simultaneously subsumed and supervened on the sociopolitical, becoming instead a kind of immaterial or diaphanous residue which could coat any imaginable life context. In modernism, the idea that anything could be art was scandalous, whereas in conceptualism, this indeterminacy became mundane.

With art more deeply yoked to culture, art became a toolkit for interacting with the lived conditions of humanity akin to a social science or school of thought. The modernist decline of art’s primacy resulted in the simultaneous expansion of art to whatever; the reduction of art to commentary on world affairs and meta-comments on its own history; and the valorization of thought as the ideal medium for aesthetic practice in this new context.

Kaprow’s concept of post-art exemplifies this, blurring the line between art and life since “nonart is more art than Art art.”8Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, 98. Whatever a person wants to get out of art, life has more of it, and art’s duty is to take on a managerial relationship to the sensory by existing in a state of fluidity, even precarity—and in this ephemeral state it haunts life, it folds all life into it. With this vastly expanded aesthetic field, thought as artistic medium engenders a process of art mimicking the disciplines of thought—namely science and philosophy.

5. An Oak Tree (1973)

It is instructive to consider a work that exemplifies the conceptualist gambit of folding thought into the set of available artistic mediums, with its resultant valorization of reason and philosophical aesthetics.

Irish artist Michael Craig-Martin’s An Oak Tree (1973) is a conceptual work consisting of a glass of water placed on a glass shelf 253 centimeters off the ground with an accompanying text.9This text was at first was handed out as a leaflet but is generally wall-mounted behind glass today. The work was first shown at the Rowan Gallery in London, 1974. In Q&A format, the text explains the artist’s process of “changing a glass of water into a full-blown oak tree without altering the accidents of the glass of water.” The oak tree resulting from this metaphysical alteration “will not ever have any other form but that of a glass of water,” and when pushed to answer the question of where the art is, Craig-Martin states in the text that this resultant oak tree is the art object.

An Oak Tree (1973) plays on the Aristotelian supremacy of essence over accident. The essence of the oak tree persists, despite all of the sensory evidence to the contrary. The ostensible transformation is not aesthetically accessible, and therefore the particular oak tree presented to the audience has no aesthetic dimension at all. Rather, the aesthetic dimension is entirely accidental to the essence which is intended for gallery display: the former is a glass of water, the latter is an oak tree.

The work also reflects the artist’s Catholic upbringing, drawing on the concept of transubstantiation. At the last supper, “Jesus took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, ‘take and eat; this is my body.’ Then he took a cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave it to them, saying, ‘Drink from it, all of you. This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.’”10Matthew 26:26-28 NIV.

At communion, Catholics ceremonially consume a cracker and wine to signify the bread and wine which at the last supper was, in essence, the flesh and blood of Christ — despite the accidents of the bread and wine. With this shade of meaning, the artist intends to “deconstruct the work of art in such a way as to reveal its single basic and essential element, belief that is the confident faith of the artist in his [sic] capacity to speak and the willing faith of the viewer in accepting what he [sic] has to say. In other words belief underlies our whole experience of art.”11Craig-Martin, Landscapes, 20.

An Oak Tree (1973) is a fine example of the conceptualist gambit and its vaunting of thought: it simultaneously extricates itself from the abject sensory, and more deeply yokes itself to it (since after all of this metaphysical transformation from a glass of water into an oak tree, the sensory dimension still indicates only a glass of water). In dissecting the social contract between artist and audience, it speaks to contemporary art as a secularized iteration of an originally theological endeavor, one which served as a litmus for humanity.

It seems to be an impossible puzzle but it’s easy to solve the Rubik’s Cube using algorithms.